The two paintings in this project are reflections of characters in Toni Morrison’s Sula. For the paintings, the mediums are collage and acrylic paint on canvas. The original goal in creating these paintings was an aim to reveal the implicit biases in each variation of a human and relate to our discussion of Sula that focused on how Morrison represents various disabilities. In the end, it became much more nuanced than that. The final works do, I hope, reveal the perspectives of disability that Morrison shows in Sula, but they also reveal the celebration of disability that Morrison creates in her text.

First, a disclaimer: Morrison creates the characters in her novel to have complex identities that include race, gender, and physical, mental, and emotional disabilities. My pieces focus on textual descriptions and circumstances surrounding disability, I am not in any way trying to speak about Black individuals’ identities and their experiences, I am just continuously inspired by Toni Morrison and her work and created these pieces in response to her text.

The physical process of creating these pieces centered around finding the appropriate clippings from magazines that I felt illustrated each idea best. In looking through the catalogs and catalogs and catalogs of magazines in my collection, the vision of the paintings comes together. The paint plays a big part in creating these pieces because color holds a lot of meaning to individuals. The left side of Sula’s piece could not just be a plain grey because her view of life still has depth. Can one properly convey madness without paying close attention to how they use the paints at their disposal? Once I finished combing through Morrison’s text, clipped the magazines, and mixed the paint, it was time to assemble the masterpieces.

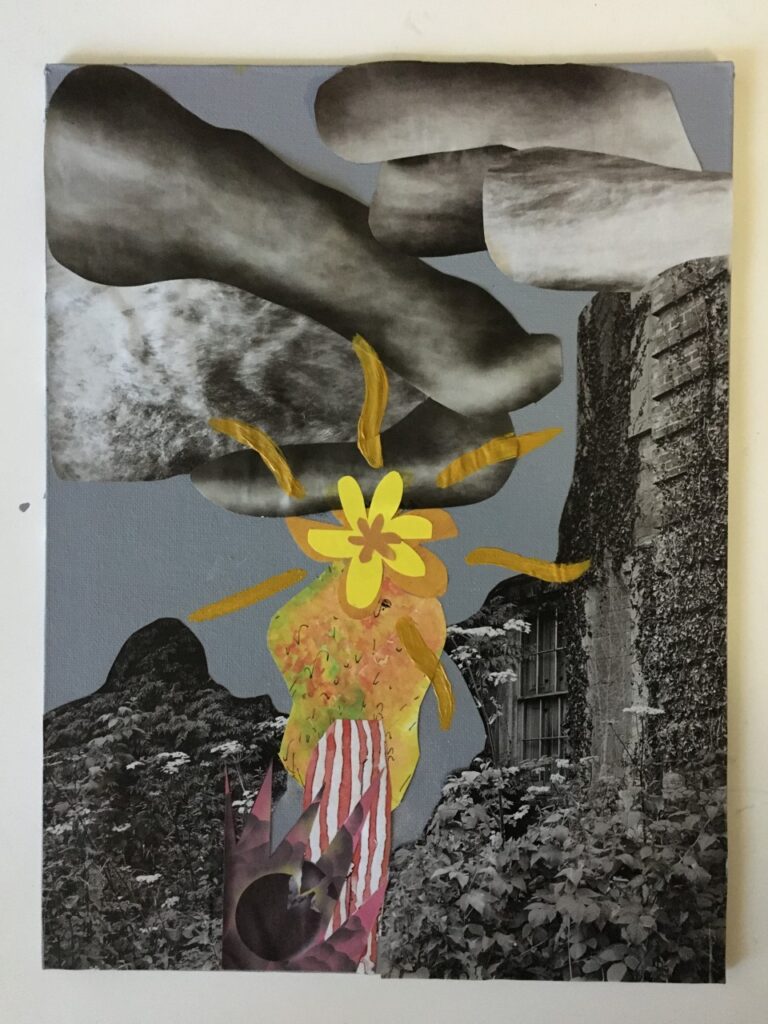

The first piece of work is an illustration of Morrison’s perspective of madness as illustrated through the character of Shadrack. The title of the piece is the quote that inspires it: “Once the people understood the boundaries and nature of his madness they could fit him, so to speak, into the scheme of things” (Morrison 15). Shadrack’s madness becomes the “fabric of life up in the Bottom of Medallion” (Morrison 16) and essentially, he fades into the background of the town, therefore the grey landscaping, grey clouds, and grey painted background show how the world exists with Shadrack; people simply “had no attitudes or feelings about Shadrack’s annual solitary parade” (Morrison 15). Morrison describes Shadrack and his “madness” on the “first… National Suicide Day” with “eyes [that] were so wild, his hair so long and matted, his voice so full of authority and thunder” (Morrison 15). Shadrack wears striped pants in the painting to represent his madness and has a small breaking bomb at the bottom of his feet as a metaphor for his “thunder” cracking the foundation of the town.

Shadrack has an ability that no one else has in the novel, he empathizes with Sula. His ability to connect and reassure Sula, an almost untouchable entity, makes him one of the sanest characters in the novel, although the town sees him as “wild”. The yellow growing out above and beyond Shadrack shows the light that Shadrack brings to Sula in providing permanence in her life with his word “always”. The spirals spanning outside of Shadrack’s yellow identity are a metaphor for his National Suicide Day. Morrison introduces the act of National Suicide Day as an act of madness, but in the end, it is Suicide Day that recognizes suffering as human because “the same folks who had sense enough to avoid Shadrack’s call were the ones who insisted on drinking themselves to death or womanizing themselves to death” (Morrison 16). Shadrack, a madness-aligned character exists as a disabled identity in the town because of his mental disabilities from the war, but also in celebrating the same day every year, he provides sanity to the people who otherwise would not receive it.

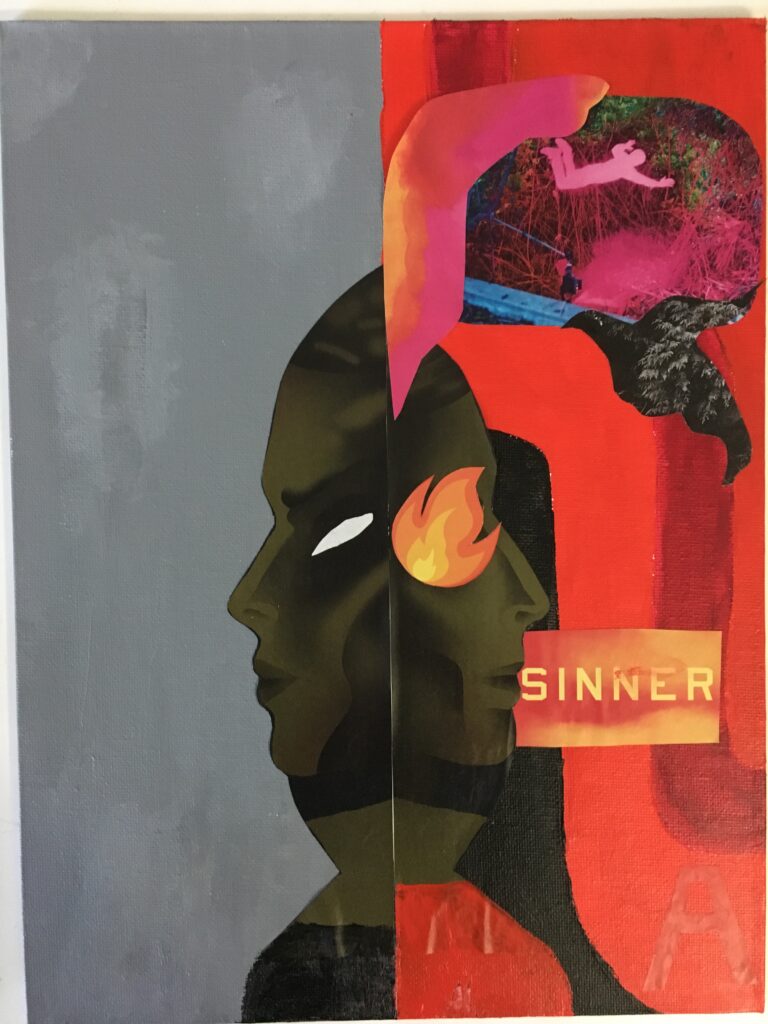

The second painting displays on the left how Sula sees the world and, on the right, how the world sees Sula. This painting is titled “Golden”. Sula exists, both through her birthmark and through her actions, as a spectacle and a body that violates the norm. Sula is a disability-aligned character because of the way others view her, she exists as “the devil in their midst” (Morrison 117). The right side of the painting reveals the spectacle and disgrace others see in Sula through the image of red representing the image of the “devil”. On this side, Sula wears a red dress, exists in a red cloud, and thinks in red thought bubbles because she is “the fourth” face of the “God of three faces they sang about” (Morrison 118). The fire, a symbol of something that continues to grow and devour surroundings, serves as a metaphor of the “birthmark that spread from the middle of the lid toward the eyebrow” which “grew darker as the years passed” (Morrison 53). This side also features a bird to represent “the plague of Robbins” (Morrison 112) with Sula’s return and a thought bubble with the image of a person jumping out of a window to represent the trauma of Hannah’s death that Sula carries with her.

The left side of the painting represents how Sula sees the world and is based on the description of Sula’s eyes at the beginning of the novel, she has “gold-flecked eyes, which, to the end, were as steady and clean as rain” (Morrison 53). Sula remarks that “the real hell of Hell is that it is forever” (Morrison 117), which shows how dull she feels forever is. Consistency is Hell and “ugliness [is] boring” (Morrison 122) and Sula’s “lonely is [hers]” (Morrison 143), so I painted the background of her perspective grey with white flecks throughout. Sula’s overall perspective on life is that it is dull and boring, which so contrasts with how the town sees her. So, the two perspectives now live in conversation together on this painting revealing how Morrison writes Sula as a disability-aligned character and uses her to illustrate implicit biases.

On the topic of implicit biases and devaluation of disabled bodies in disability studies is Snyder and Mitchell’s Introduction to Cultural Locations of Disability. Snyder and Mitchell discuss that “the devaluation of disabled bodies places in jeopardy all bodies that exist within proximity to ‘deviance’” (Snyder and Mitchell 5). This relates to my illustration of Sula because she exists less as a disabled body and more so as a deviant body in Morrison’s text and it is her “deviance” that marks her identity in the town, as illustrated on the right side of “Golden”. More so, Snyder and Mitchell discuss the cultural model of disability and come to an “understanding that impairment is both human variation encountering environmental obstacles and socially mediated difference that lends group identity” (Mitchell and Snyder 10). The idea of impairment as something that is socially mediated is relevant to my discussion earlier of Shadrack’s othering at the hands of the town. Shadrack exists as an othered body because “Once the people understood the boundaries and nature of his madness they could fit him, so to speak, into the scheme of things” (Morrison 15). Shadrack’s disability is, in part, a result of social mediation and how they designated him in society, which is visible in my portrait of him. The paintings reveal the idea of implicit biases of disabled bodies and Mitchell and Snyder’s discussion of “deviance” and how society deems what is acceptable and in what category it is.

1252 words

I pledge- Rachel Grace Chaos

Works Cited

Morrison, Toni. Sula. Vintage Classics, 2020. Print.

Snyder, Sharon L., and David T. Mitchell. Cultural Locations of Disability. The University of Chicago Press, 2015. Print.